Climate change and migration: What we know about the connection and what options there are for action

Annual Report 2023

The SVR Annual Report Summary 2023 can be downloaded here.

Climate change is one of the greatest challenges faced by humanity. Global warming has complex and, for all aspects of life, existential consequences. Global, regional and local migration patterns are changing too. Migration as a direct consequence of climate change (known as climate change-induced migration) is increasing, but how and to what extent it takes place depends on a number of factors. Where, how and how fast is the climate changing? What measures are individual states and the global community taking to halt global warming and achieve agreed climate goals? How are people and states in different parts of the world dealing with progressing climate change and what measures are being taken to adapt? How consistently is climate change-related hardship being addressed? Will disaster prevention be made more of a priority? And will the burdens resulting from climate change be distributed more fairly – burdens which are currently borne disproportionately by the already disadvantaged countries of the global South?

In its 2023 Annual Report, the Expert Council on Integration and Migration (SVR) addresses the questions of what we know about climate change-induced migration and what actions can be taken. At all political levels – national, regional and international – considerations relating to migration and refugee policy have begun to play a bigger role in the overall discourse on climate change. Nevertheless, these issues still do not receive sufficient attention. A global framework for action is still lacking. This is why nation states in particular are called upon to work towards coordinated solutions at the international level. Such solutions can be based on innovative national measures that in turn, can serve as models for policies at the supranational level.

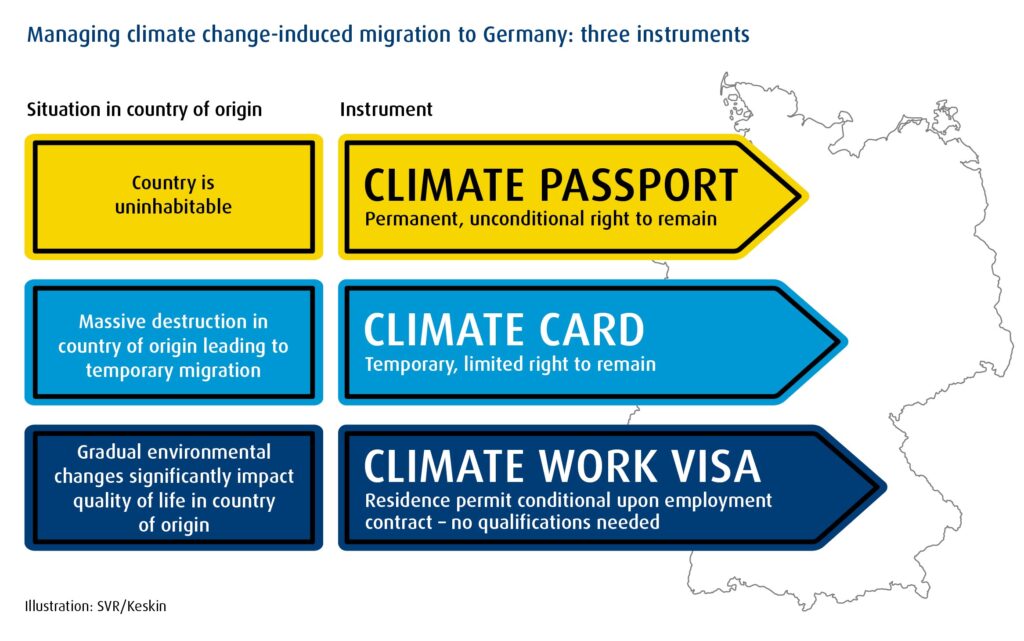

To meet the challenges of climate change-induced migration, the SVR is proposing three instruments to political decision-makers in Germany: a climate passport, a climate card and a climate work visa.

The idea of creating a climate passport was originally put forward by the German Advisory Council on Global Change. The SVR’s proposal, as set out in the Annual Report, builds on the original concept, add-ing more details and making it more specific. The climate passport would be offered to people from countries that are losing their entire territory as a result of climate change. These individuals would be granted a permanent right to remain. The climate card is designed for individuals who need to leave their country temporarily as a result of environmental devastation; with a broader scope of application than the climate passport, this instrument would require a country-specific quota, and would represent a temporary leave to remain modelled on humanitarian admission programmes. Use of the instrument would be conditional upon adaptation measures being implemented in parallel in the respective countries of origin, so that a return would be possible in the long term. The climate work visa, which could be used as a mean of offering easier access to the German labour market, would be applicable to a limited con-tingent of people from countries still to be named, similarly to the Western Balkans regulation. The aim is to open up new perspectives to people affected by climate change through alternative sources of income.

The consequences of human-created climate change demand a swift response. This urgent need for action applies at every tier of politics and many policy fields, but also to the economy and society. The issues at stake are well known. The decisive factor will be how quickly and to what extent CO2 emissions are limited worldwide so that there is still a chance of achieving the Paris climate goals. All industrialised nations, and thus also Germany, bear a special responsibility here.

Nine Core Messages

1. Climate change reinforces existing drivers of migration

Specific environmental disasters cannot always be clearly attributed to climate change, and environmental changes cannot generally be isolated from other factors that may trigger flight or displacement. However, a look at current research shows that climate change-induced alterations in the environment and extreme weather events exacerbate existing social, economic and political pressures. As a result, they can also increase the pressure to migrate. If the fight against climate change and its consequences fails, migration will necessarily increase. However, climate change-induced migration is not a new and clearly defined form of migration. Rather, it is closely interwoven with other forms of migration in terms of its causes and the underlying motives of individuals migrating.

In the future, connections between climate change and migration must be recorded more precisely and at an earlier stage to enable governments to respond. This requires, among other things, further research. Such research should not so much aim to identify precise figures in relation to climate change-induced migration; achieving such a goal continues to be problematic, as the interplay of the various factors is complex and in some cases no suitable data are available (see also Core Message 3). However, empirical studies and comprehensive data can help to drill down into the specific dynamics of climate change-induced migration and the risk factors for increased vulnerability. Research acts as an interface here; it can and should help decision-makers, as well as those affected, to develop sustainable adaptation strategies.

For more information, see Chapters A.1.2 and A.2.1.

2. Climate change-induced migration is mostly internal or to neighbouring countries, rarely across continents

The countries of the global South are particularly affected by the consequences of climate change. This is not only due to their geographical location, but also to the fact that they have fewer financial resources to draw upon. Economically strong countries – which are historically and currently especially responsible for the advance of climate change – can afford, for example, early warning systems, disaster protection, and reconstruction and compensation measures. In poorer countries, on the other hand, which bear less historical responsibility in this matter, the necessary funds for such measures are usually lacking. It is thus not only the risks that are unequally and unfairly distributed across the globe, but also the opportunities to adapt to climate change. Here, it is essential to identify and implement fair solutions. People – and countries – that are especially vulnerable must not be left alone with the threats and the efforts required to deal with them.

For further information and recommendations, see Chapter A.2, especially A.2.1.1.

3. Migration due to climate change will increase, even if forecasts are fraught with uncertainty

Forecasts and possible scenarios continue to be important instruments for forward-looking political action. They provide orientation and can highlight the areas where urgent action is needed. However, they cannot predict with absolute certainty how climate change-induced migration will develop in the future. This is due in part to data gaps, but also because individual migration decisions depend on numerous factors. Last but not least, there are also a number of unanswered questions regarding the further development of climate change. When and to what extent will carbon emissions be reduced? Where are adaptation measures taking place, such as the implementation of coastal defence systems or a transition to the use of drought-resistant plant varieties in agriculture? How do people choose to act in response to environmental change, and what decisions do they make for themselves and their families? Predictions about climate change-induced migration can differ significantly, depending on the assumptions that are made about how fast climate change will develop and how people affected by it will react, what methodologies are used to collect the data and which data are taken into account.

However, even if the extent of climate change-induced migration cannot be predicted in detail, all available projections and scenarios point unequivocally in one direction: advancing climate change will lead to more migration overall. According to the second Groundswell Report from 2021, even an optimistic projection could still see more than 40 million people forced to leave their homes, while a pessimistic reading would put this figure at well over 200 million. Those affected will predominantly move within their home country or to neighbouring states, but migration between continents will also increase. Despite their differences, however, current forecasts and scenarios unanimously show that there is an urgent need for political action. If no effective climate protection is implemented, and too little is invested in sustainable development and adaptation to the unavoidable consequences of climate change, significantly more people will have to migrate in the future.

Forecasts and scenarios are a key tool for decision-makers in shaping long-term and forward-looking policies. However, such estimates can also easily be taken out of context and instrumentalised. Therefore, the SVR believes it is very important that the scientific community presents and classifies forecasts and scenarios on this topic in a responsible manner. Actors in the media and in politics must demonstrate equal responsibility in how they respond, and must handle such predictions sensitively. To further this end, it is essential that the underlying premises of the research and the methodologies chosen, as well as remaining areas of uncertainty and the limitations of the science, are communicated transparently.

For more information and recommendations, see Chapter A.3.

4. States should protect the right to remain while enabling migration as an adaptation strategy

Economically disadvantaged population groups are usually most affected by the impacts of climate change. At the same time, they have only limited opportunities to adapt to them in a way that is sustainable in the long term. Migration can be one adaptation strategy. However, to be effective and sustainable, it requires financial resources, education and/or professional qualifications, or even a personal network. People who are dependent on natural resources, such as those whose main source of income is agriculture or fishing, usually do not have sufficient means to start anew in another place. After migrating, they often find themselves in precarious employment and living conditions. Others simply lack the money to migrate, and as a result become ‘trapped populations’.

Migration in the context of climate change should therefore be understood not only as a problem to be prevented, but also as a proactive adaptation strategy. For example, remittances to family members in the country of origin can compensate for the reduced income of the latter, enable investments to reduce dependency on weather events or support adaptation to new environmental conditions. In a similar way, migration should be facilitated by national governments as an investment in a sustainable future and accompanied by comprehensive integration measures, using the entire range of migration policy instruments to do so (see also Core Message 5).

At the same time, the needs of those who do not want to migrate because of a close attachment to a place, a culture or their familiar community must be taken into account. The SVR therefore recommends investing in adaptation strategies and designing them in such a way that remaining in the country or region of origin is not only possible, but also worthwhile from the point of view of those affected. The right to remain, and the realistic possibility of doing so, must be strengthened – for example, through increased climate protection, the expansion of disaster preparedness and needs-based adaptation measures on the ground.

For more information and recommendations, see Chapter A.2, especially A.2.1.2.

5. Shaping climate change-induced migration requires engagement at all levels of government, using the entire range of migration policy instruments

Climate change-induced migration policy can only be shaped responsibly if its multi-layered framework conditions and its different manifestations are fully acknowledged. This requires the use of the entire range of available migration policy instruments. Where sudden (often temporary) migration cannot be avoided, for example where people need to escape an impending environmental disaster or its consequences, it may be useful to apply approaches that are more familiar from the field of refugee policy in its broadest sense. Such options may include, for example, the use of humanitarian visas or temporary legal protection, but also the suspension of repatriations to countries and regions affected by disasters. However, when it comes to enabling migration as a targeted adaptation strategy, migration policy instruments are more likely to be useful. These could be, for example, work visas or existing agreements on free movement of persons which allow people affected by climate change access to other countries (see also Core Messages 7 and 8).

In activating such instruments, all political levels – from the local to the global – must be involved. The different tiers, whether global, regional, national or local, should work in an interlinked and coordinated manner. The national level is particularly important here; regional or global forums can make recommendations or adopt agreements, but it is up to national governments to implement them. So far, the ability to formulate and implement a common policy approach at the global level has been lacking (see also Core Message 6). The SVR recommends that Germany should lead the way in promoting international cooperation within the EU and in global forums and, in addition, should develop new approaches to solutions in close coordination with the countries concerned (see also Core Message 8).

In shaping policy, questions of justice must also be taken into account. Responsibility for climate change is, in general, borne by those who do not suffer the worst effects of it. This injustice, which has brought about immense inequality, holds true both at a global level and within societies (see also Core Message 2). Countries that historically have high CO2 emissions and consume many natural resources therefore have a special responsibility to drive forward climate protection and to support other countries financially and technologically (for example through technology transfer), or through new opportunities for migration, in order to fairly manage the consequences that arise as a result of climate change.

For further information and recommendations, see Chapters B.1.2, B.2 and B.3.

6. Instead of relying on new agreements, existing global agreements should be applied nationally and regionally

Climate change, flight and migration are global challenges. However, a form of ‘global governance for climate migration’ does not yet exist. Legally binding instruments of international law such as the Geneva Refugee Convention can only be applied to climate change-related migration to a limited extent; the same applies to the human rights principle of non-refoulement. For this reason, one proposal has been to create new regulations under international law that oblige states to grant protection to ‘climate refugees’. A binding mechanism for this, however, could not be created without first overcoming considerable political hurdles. A renegotiation of the Geneva Refugee Convention would currently have little realistic chance of success. In many countries, the laws in relation to refugees are subject to increasingly restrictive interpretation; in some places they are effectively disregarded. The SVR therefore sees a high risk that renegotiating global agreements would not strengthen the existing protection regime, but rather weaken it.

Apart from binding agreements, however, various informal cooperation frameworks at the international level already exist that provide a good basis for migration and refugee policy approaches in the context of climate change-induced migration. These include the Global Compact for Migration, the Platform on Disaster Displacement and the Task Force on Displacement. Within this framework, states, international organisations and the scientific community have developed comprehensive guidelines and recommendations for action on climate change-induced migration.

The SVR recommends that migration and refugee policy strategies should be adapted to factor in climate change-induced migration, using existing structures and recommendations for action to tailor such strategies more precisely to concrete situations and to implement them effectively. This is especially relevant with regard to those countries and regions that are already suffering greatly from the consequences of global warming. The SVR believes that a mosaic of local, regional and national approaches is better suited and more realistic than a global instrument that would have to be newly developed and negotiated. Nevertheless, the ability to act at a global level must be strengthened. To this end, the SVR recommends monitoring the implementation of the existing recommendations for action more closely and improving political coordination between national governments. The measures proposed in the Global Compact for Migration to deal with climate change-induced migration could serve as a basis for such monitoring. Existing solution-based approaches identified by various processes and forums should be consolidated in order to make these more easily accessible.

For further information and recommendations, see Chapter B.2.

7. Promote regional solutions

Cross-border climate change-induced migration often takes place between neighbouring countries (see also Core Message 2). This is one reason why the regional level of governance plays a special role in addressing this kind of migration. Moreover, regional solutions are more realistic, pragmatic and quicker to implement than global ones. In particular, refugee protection and agreements on the free movement of persons can facilitate dignified and regulated migration, sometimes also enabling anticipatory migration. Examples from Latin America and Africa show that both instruments can be applied to climate change-induced migration.

However, people who migrate as a result of climate change face major challenges, as do the destination countries. If people migrate from one particularly vulnerable country to another, they face the risk of repeated displacement and social marginalisation. Here, again, the question of climate justice arises. How, for example, can the industrialised nations, including Germany and the other EU member states, support regional solutions in other parts of the world? An important element in this would be financial and technological transfers to countries that have contributed little to climate change but are disproportionately affected by its consequences.

In the EU, existing asylum and migration policy instruments can be shaped in such a way that they are applicable to climate change-induced migration – instruments such as the EU Directive on Temporary Protection, activated for the first time in 2022, the implementation of resettlement programmes and the granting of humanitarian visas. Above all, however, development cooperation programmes can be used at the EU level to promote adaptation to climate change in affected countries and regions and to support countries with high levels of internal migration. Independently of the European debate, Germany should take a pioneering role here and develop innovative new instruments (see also Core Message 8). Such initiatives can be coordinated with other states in a ‘coalition of the willing’, sending a clear message. In this way, they could also be implemented at the European and global level in the long term.

For further information and recommendations, see Chapter B.3.

8. Germany as pioneer: three migration policy instruments

Climate change requires rapid and immediate responses. Such responses are initially most likely to come from national governments. The SVR proposes a combination of three instruments that could be used by policy-makers in Germany to act effectively: a climate passport, a climate card and a climate work visa.

- The climate passport would be the most robust of the three instruments in terms of residence law. Following a corresponding proposal of the German Advisory Council on Global Change, the SVR recommends granting such a passport to a clearly and narrowly defined group of persons: nationals of countries that are directly affected by climate change and losing their entire territory as a result (e.g. nationals of sinking Pacific islands). Such individuals should be able to obtain a humanitarian permanent right of residence in Germany. With a climate passport, Germany, as an industrialised country, would assume co-responsibility for climate change and could coordinate with other industrialised countries in this regard.

- The climate card would be aimed at people from countries that are significantly affected by climate change but are not under existential threat. It is intended to enable individuals from such countries to come to Germany, initially for a limited period of time. The group of eligible persons would be significantly larger than with the climate passport, and as such, this proposal would require a country-specific quota system. In this way, immigration via the climate card could be planned, similarly to humanitarian admission programmes. The selection of eligible countries would be the responsibility of the receiving country, in this case the German Federal Government. The climate card instrument would need to be combined with adaptation measures in the respective countries of origin so that it can be effective and people who have received a climate card can eventually return to their home countries.

- The climate work visa would be aimed at people from countries that are affected by climate change to a much lesser extent than those eligible for the first two instruments. This labour migration instrument could break new ground. Nationals of certain countries would be given easier access to the German labour market, opening up new sources of income and perspectives to them through regular migration. The residence title would be conditional upon the existence of an employment contract, without the need to evidence specific qualifications or language skills. The so-called Western Balkans regulation, which has been anchored in German law since 2015, could serve as a model here.

For further information and recommendations, see Chapter B.4.

9. Use migration policy as a building block in an overall strategy to mitigate climate change and its consequences

Mitigating climate change and its consequences requires an overarching strategy. The use of measures from the entire spectrum of migration policy, as recommended by the SVR, must be understood as a building block in this. Such an overarching strategy must above all include a consistent climate policy, which in turn must integrate a coherent external climate policy involving migration policy aspects and supported by all relevant ministries. In addition, financial agreements must be reached, for example on global funds. Likewise, global risk management must be established and expanded, and development policy approaches must be developed and implemented to promote adaptation measures on the ground. The costs of these measures must be distributed fairly worldwide. A coherent overall approach therefore requires action both on climate change, and on climate change-induced migration, to be coordinated across ministries at the national level. But at the EU and international level, too, the interactions between different policy fields must take greater priority than they have done to date.

For further information and recommendations, see Chapter B.1.2.

The nine core messages of the annual report 2023 as PDF.

The press release of the annual report 2023 can be downloaded here.